fasting alternative

What is Carbohydrate Loading in Surgery?

Preoperative carbohydrate loading is an evidence-based strategy to improve patient outcomes and expedite recovery. Enhanced recovery programs have implemented carbohydrate loading as an effective nutritional strategy aimed at reducing post-operative stress and improving the recovery process.

Definition

Carb loading in surgery is defined as consuming a clear fluid containing:

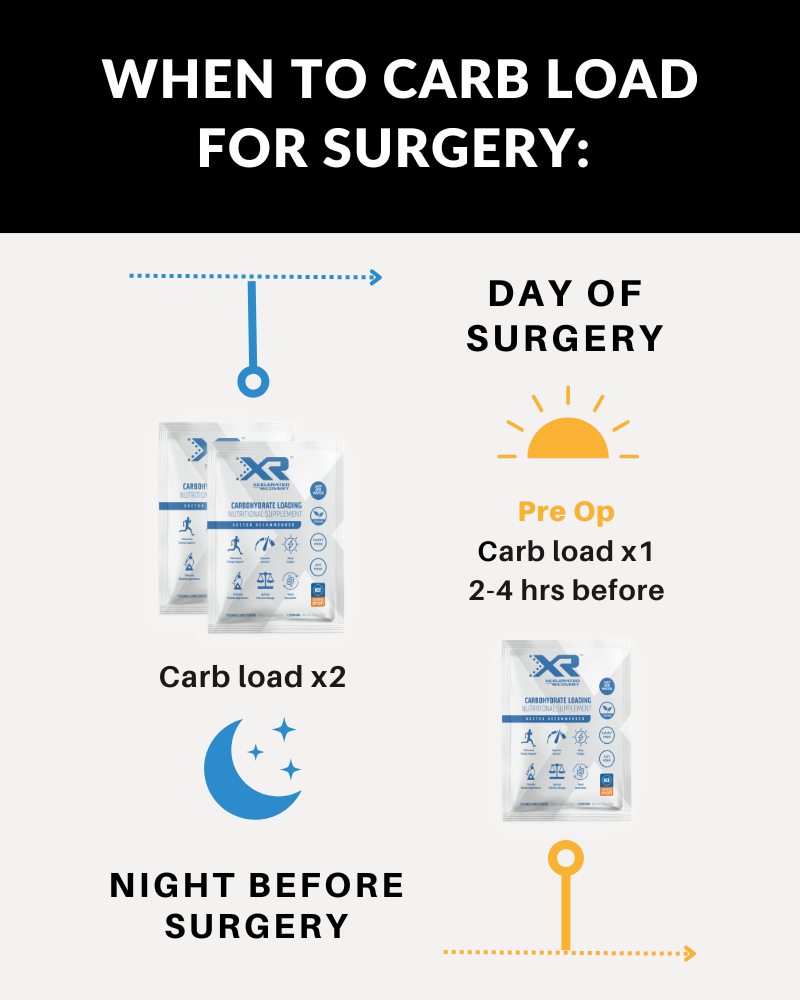

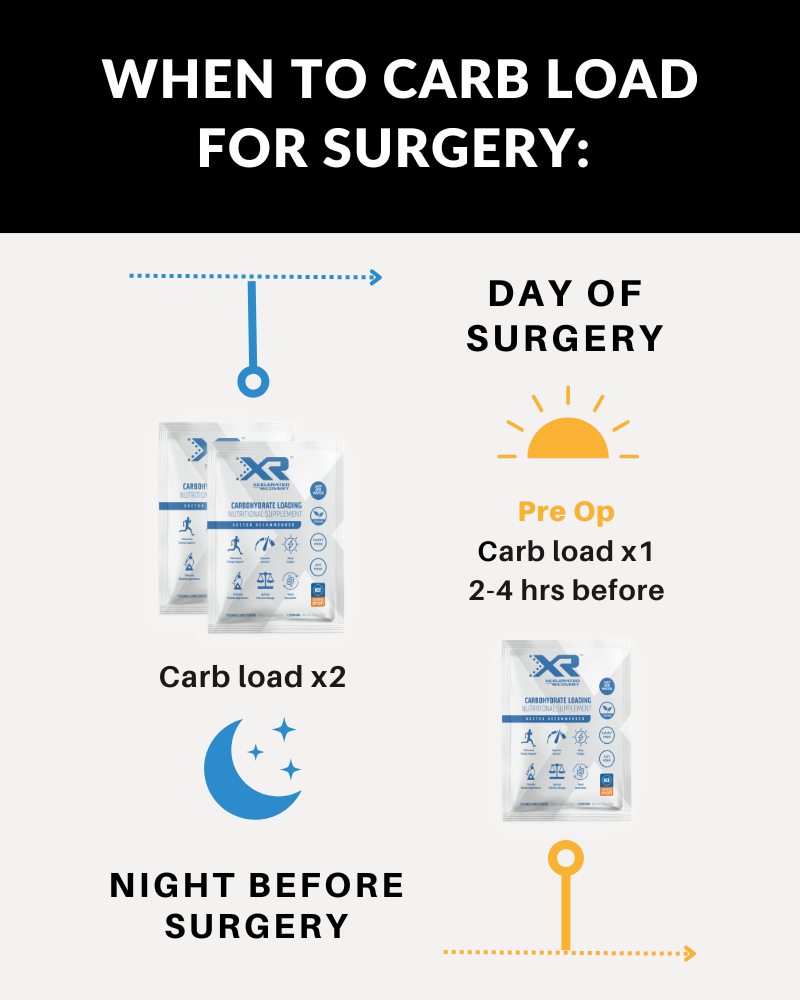

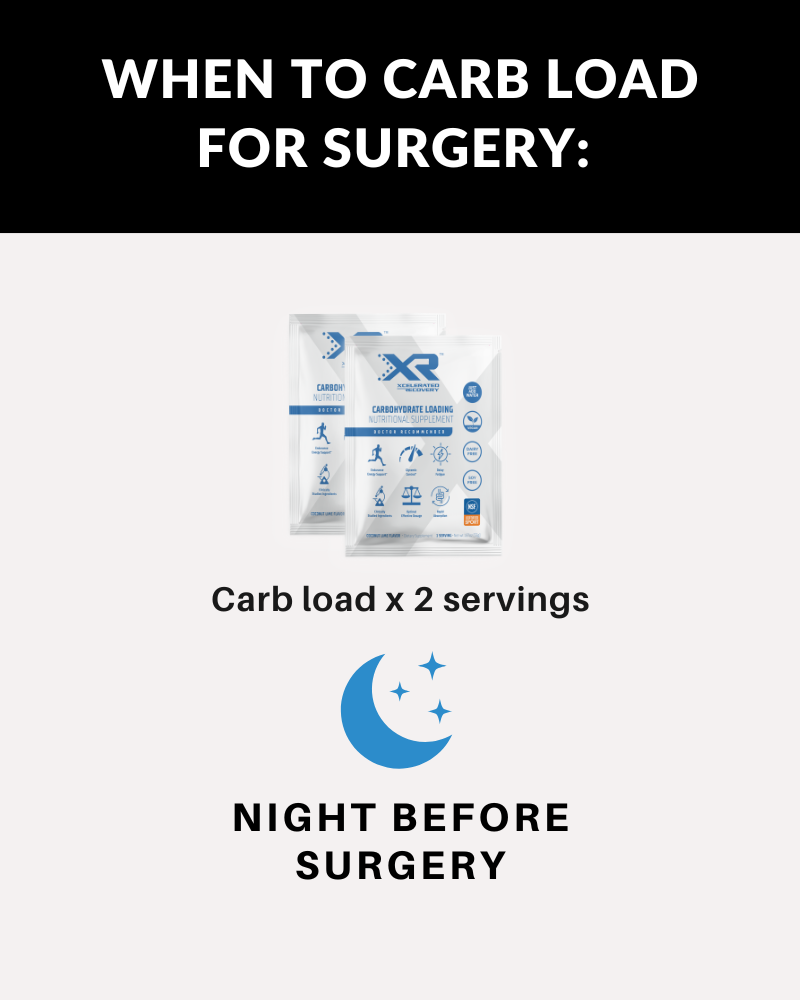

- Loading dose: 100 grams of complex carbohydrates (2 x 50 gram packs) each mixed in 400 mL of water the evening before surgery. (Optimizes liver glycogen storage)

- Pre-anesthesia dose: 50 grams of complex carbohydrates (1 x 50 gram pack) mixed in 400 mL of water 2-3 hours prior to anesthesia. (Places body into fed state)

Carbohydrate loading is a modern alternative to preoperative fasting (NPO) protocols utilizing an anesthesia approved maltodextrin formulation. This approach prepares patients for the metabolic demands of surgery by providing a sustained energy source and placing patients in a metabolically nourished state. Similar to an athlete preparing for a competitive event, the goal of carbohydrate loading is to be optimally fueled to face the metabolic stress of surgery.

science

Evidence-Based Foundation

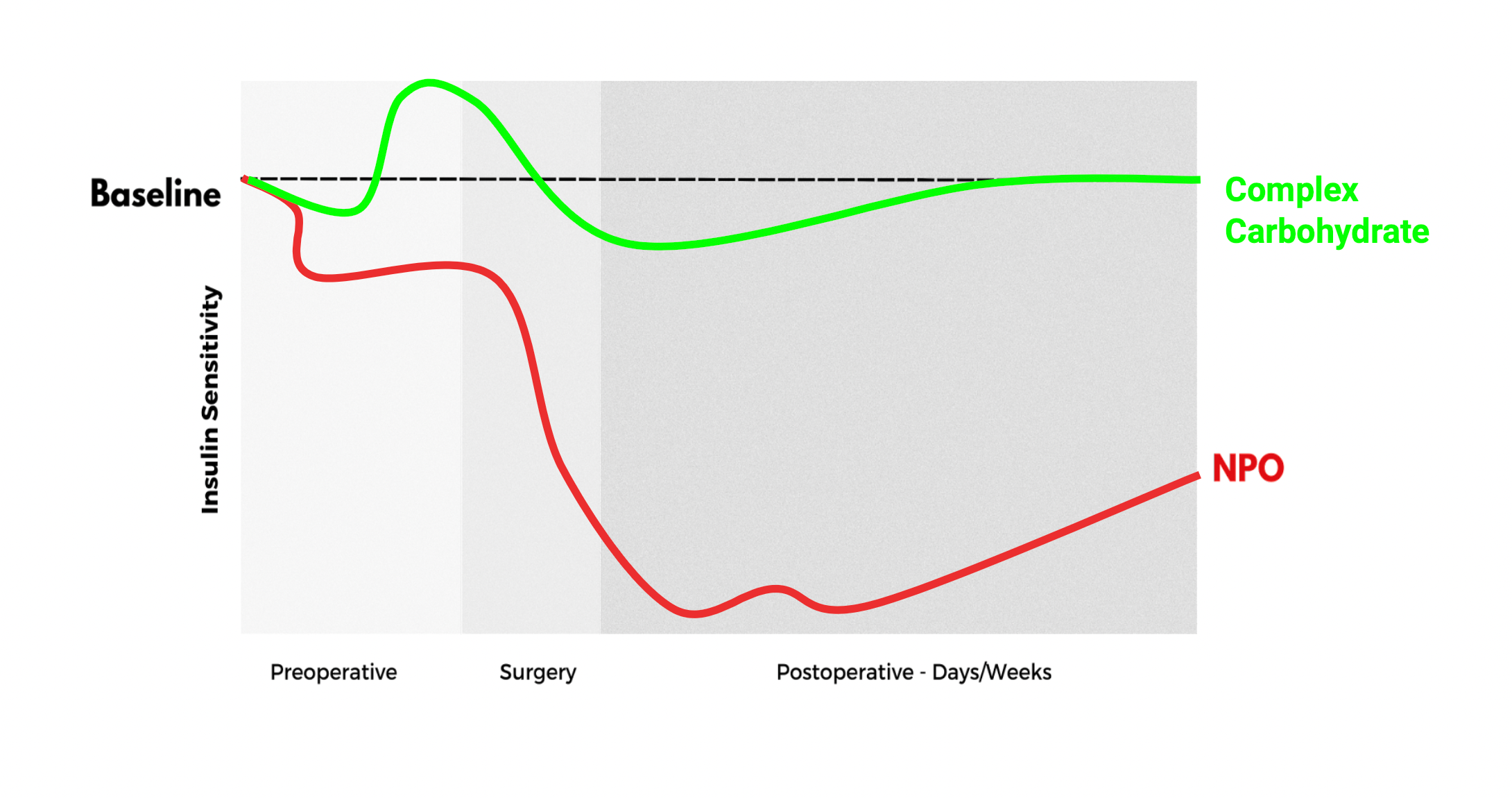

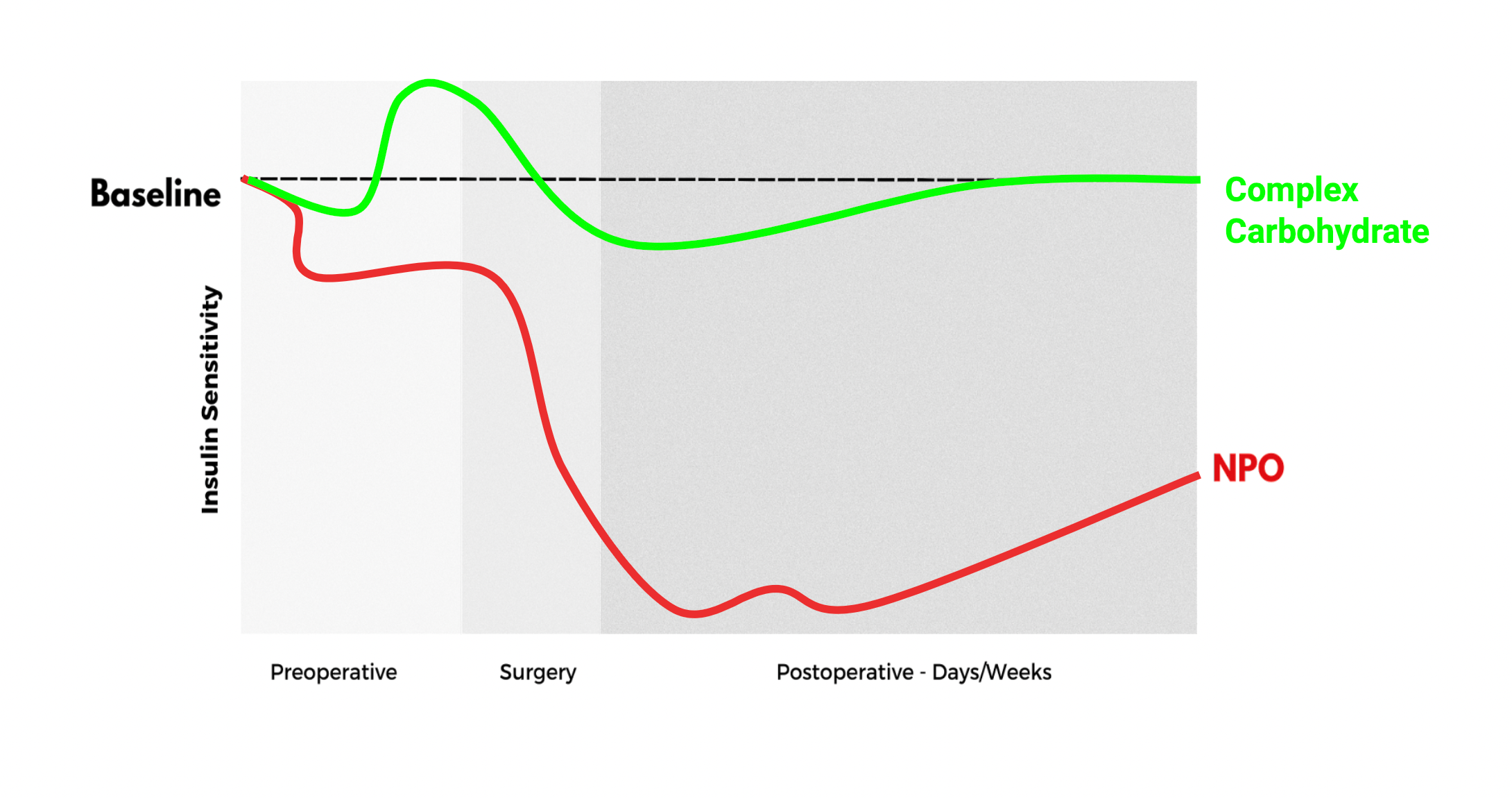

The combination of being in a fasted state and the surgical stress response leads to an elevated catabolic cascade resulting in decreased insulin sensitivity and increased skeletal muscle breakdown.

Carbohydrate loading shifts the body out of the fasted state and into a fed state, which has been demonstrated to promote metabolic regularity, insulin stability, preservation of lean body mass, decrease myocardial ischemia, expedite recovery and decreased postoperative complications.

details

Product Facts

- Flavor: Refreshing Coconut Lime

- Carbohydrate Content: 50g maltodextrin per serving

- Low Osmolality: 114 mOsmol/kg H20

- Mixing Convenience: Mix easily with water

- Exclusions: Deliberate absence of protein and fat

- Storage Ease: No refrigeration require delays

- Recommended for: all elective surgical procedures unless specifically contraindicated

Benefits

-

REDUCE

- Insulin resistance (improved glycemic control)

- Infection

- Thirst & hunger

- Length of stay

- Anxiety and stress

- Protein loss

-

IMPROVE

- Faster recovery

- Immune response

- Improved patient care

- Support muscle strength

- Preserved lean body mass

-

Evolving (NPO) Protocols

Traditional fasting (NPO) protocols are no longer supported by current anesthesia recommendations, and the use of preoperative carbohydrate loading has been established to be safe with no increased risk of aspirations, delayed gastric emptying or complications.

Collapsible content

Can People with Type 1 Diabetes Consume Carbohydrate Loading?

No, individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes should not consume Carbohydrate Loading.

People with type 1 diabetes suffer from a chronic ailment characterized by insufficient or absent pancreatic insulin production, a hormone responsible for facilitating sugar absorption into cells for energy. Consequently, Carbohydrate Loading consumption will not induce the desired insulin response in this group.

Can Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Utilize Carbohydrate Loading?

In most cases, individuals with well controlled type 2 diabetes can consider using Carbohydrate Loading.

Generally, the decision on whether Carbohydrate Loading is suitable for these patients is made by healthcare professionals or clinicians. There is substantial evidence supporting the safety of preoperative carbohydrate loading in patients with well controlled type II diabetes, demonstrating that when compared to non-diabetic individuals:

- Both groups exhibit similar gastric emptying times.

- No disparities are observed between diet/oral medication controlled diabetes and insulin-controlled diabetes.

- No correlation is found between gastric emptying, glucose concentrations, or HbA1c levels.20

Contraindications

Not Suitable for Individuals with:

- Gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying

- Comorbidity that affects gastric emptying

- Type 1 diabetes

- Uncontrolled Type 2 DM

- Corn allergy

- Not for Intravenous Use

- Not Suitable as a Sole Source of Nutrition

*Determination of usage should be made by a qualified healthcare professional.

Research References

- Talutis SD, Lee SY, Cheng D, Rosenkranz P, Alexanian SM, McAneny D. The impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on patients with type II diabetes in an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Am J Surg. 2020 Oct;220(4):999-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.03.032. Epub 2020 Mar 30. PMID: 32252984.

- Lee S, Sohn JY, Lee HJ, Yoon S, Bahk JH, Kim BR. Effect of pre-operative carbohydrate loading on aspiration risk evaluated with ultrasonography in type 2 diabetes patients: a prospective observational pilot study. Sci Rep. 2022 Oct 20;12(1):17521. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-21696-1. PMID: 36266449; PMCID: PMC9584891.

- Gillis C, Carli F. Promoting Perioperative Metabolic and Nutritional Care. Anesthesiology. 2015 Dec;123(6):1455-72. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000795. PMID: 26248016.

- Robinson KN, Cassady BA, Hegazi RA, Wischmeyer PE. Preoperative carbohydrate loading in surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: Are concerns supported by data? Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021 Oct;45:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.08.023. Epub 2021 Sep 3. PMID: 34620304.

- Choi, Yong Seon MD, PhD; Cho, Byung Woo MD; Kim, Hye Jin MD; Lee, Yong Suk MD; Park, Kwan Kyu MD, PhD; Lee, Bora MD, PhD. Effect of Preoperative Oral Carbohydrates on Insulin Resistance in Older Adults Who Underwent Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 30(20):p 971-978, October 15, 2022. | DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00656

- Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review DK Bilku, AR Dennison, TC Hall, MS Metcalfe, G Garcea University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, UKhttps://mssic.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Preoperative-Carbohydrate-Loading.pdf

- Smith MD, McCall J, Plank L, Herbison GP, Soop M, Nygren J. Preoperative carbohydrate treatment for enhancing recovery after elective surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD009161. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009161.pub2. Accessed 17 January 2023. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009161.pub2/references

- Aronsson A, Al-Ani NA, Brismar K, Hedström M. A carbohydrate-rich drink shortly before surgery affected IGF-I bioavailability after a total hip replacement. A double-blind placebo controlled study on 29 patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009 Apr;21(2):97-101. doi: 10.1007/BF03325216. PMID: 19448380. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19448380/

- Shin S, Choi YS, Shin H, Yang IH, Park KK, Kwon HM, Kang B, Kim SY.Preoperative Carbohydrate Drinks Do Not Decrease Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Type 2 Diabetic Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty-A Randomized Controlled Trial.J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021 Jan 1;29(1):35-43. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00089.

- He Y, Tang X, Ning N, Chen J, Li P, Kang P. Effects of Preoperative Oral Electrolyte-Carbohydrate Nutrition Supplement on Postoperative Outcomes in Elderly Patients Receiving Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthop Surg. 2022 Oct;14(10):2535-2544. Doi: 10.1111/os.13424. Epub 2022 Aug 30. PMID: 36040184; PMCID: PMC9531096.

- Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon K. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(8):739-747.

- Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review DK Bilku, AR Dennison, TC Hall, MS Metcalfe, G Garcea

- Gustafsson UO, Nygren J, Thorell A, Soop M, Hellström PM, Ljungqvist O, Hagström-Toft E. Pre-operative carbohydrate loading may be used in type 2 diabetes patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008 Aug;52(7):946-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01599.x. Epub 2008 Mar 7. PMID: 18331374.

- European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (ESAIC). News from the ESAIC Guideline Task Force on Perioperative Fasting in Adults. Available at: https://esaic.org/news-from-the-esaic-guideline-task-force-on-perioperative-fasting-in-adults. Accessed January 20, 2025.

- Mendelson, C. L. (1946). The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 52(2), 191–205. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(16)39874-9.

Key Advantages

-

Enhanced Recovery:

Mitigated risk of complications, reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting, and expedited recovery times.

-

Metabolic Optimization:

Mitigating catabolic stress response and reduction of postoperative insulin resistance risk.

-

Patient-Centric Wellness:

Alleviated stress, optimized hydration, and tempering of surgical stress response.

-

ERAS® Alignment:

Adherence to Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines for clear liquids fluids.

-

ASA Guidelines:

Meets guidelines for use with pre-op fasting per the American Society Of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

Protocol Options

-

Protocol 1:

Evening Before Surgery:

- Drink 2 servings separately before bedtime.

Morning of Surgery:

- Drink 1 serving up to 2 hours pre op.

NOTE: You must complete the pre-op carb loading up to 2 hours before your surgical time to avoid delays.

-

Protocol 2:

Evening Before Surgery:

- Drink 2 servings separately before bedtime.

Mix with 14oz room temperature WATER ONLY until dissolved. Add ice to chill as desired.

History of (NPO) Fasting

The practice of preoperative fasting, commonly referred to as "nil per os" (NPO) after midnight, has its origins in obstetric anesthesia. In 1946, Dr. Curtis Lester Mendelson, an obstetrician, published a landmark study detailing 66 cases of aspiration of gastric contents during anesthesia among 44,016 pregnant women. This represented a complication rate of approximately 0.15%, with two fatalities attributed to aspiration of solid food. Based on these findings, Mendelson hypothesized that prolonged fasting would empty the stomach and thereby reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonitis during anesthesia. His work profoundly influenced anesthetic protocols, leading to the widespread adoption of NPO after midnight guidelines for all surgical patients, irrespective of their individual risk factors or procedure type [14, 15].

While the primary intent of this practice was to minimize stomach content volume and acidity to prevent aspiration pneumonitis, subsequent research has called its efficacy into question. Prolonged fasting has been shown to result in dehydration, insulin resistance, increased physiological stress responses, and other postoperative complications. Evidence now demonstrates that clear liquids are emptied from the stomach rapidly, with a half-life of approximately 10 minutes, indicating that allowing clear fluids up to two hours before anesthesia does not increase aspiration risk [15].